In this post, I try to get closer to what I mean by “meandering writing” or “meandering essay”. To do this, I’ll take a look at the prototype I published here a few weeks ago and try to understand the functions of the individual components in the text.

Components of a meandering essay

These are the types of elements a meandering essay can consist of.

Intro and Outro

Personal depictions from memories, experiences

Conclusions

Transitions

External knowledge, gathered from media

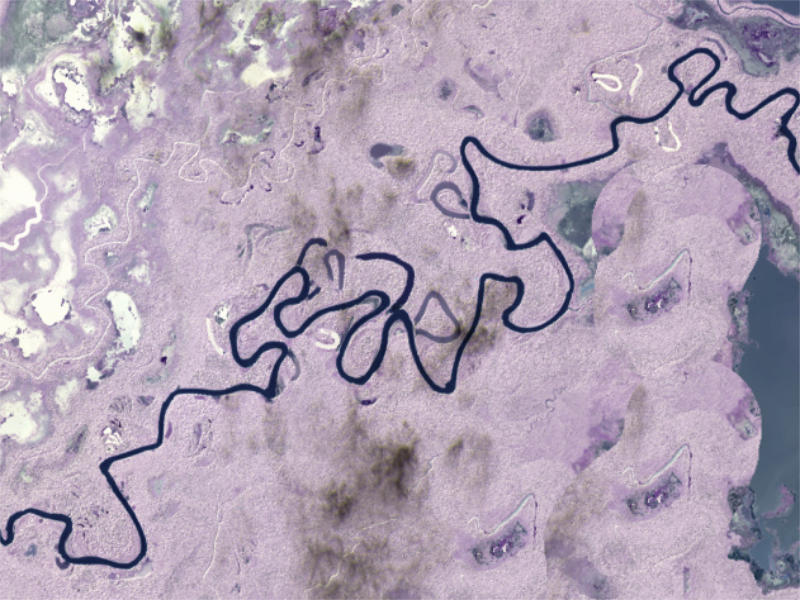

Meandering Thoughts on Low Technology – A structural overview

This is a simplified map of the structure of the text.

Introduction through a story

Experience: lowtech

Conclusion

lowtech in art

lowtech manifesto

Monica Losada

Ancient philosophy

Outro

Meandering Thoughts on Low Technology – Commented text

In the first part I tell a personal story that serves as an introduction to the essay.

In an academic essay, this part would include a thesis statement and/or a question. But because of the meandering writing approached, this is not necessary. It enables the text to meander in any direction I want.

A few years ago, I received an old Macbook Air from 2011 as a gift from my mother. It was basically useless because the operating system could no longer be upgraded and important applications such as the web browser no longer worked. At first I thought the device was just a piece of junk. But then I thought it was a real pity and started thinking about how I could rescue it.

I found a way: the trick was to install an open source operating system. There are a lot of them out there, and I picked “Ubuntu” because it is very similar to the user interface and functionality of Mac OS. Admittedly, the installation was a bit of an edgy experience, I had to record a USB stick with a huge file and then restart the MacBook with a special key combination to boot it from this stick. But after adding a few extra programs, I had a fully functional computer on my desk that didn’t cost me a penny. I was absolutely thrilled.

The following part goes more into details and tells more about the direction of the text and touches on the first node, which is a set of external resources (Kris de Decker, Hackernews). I drop a few first hyperlinks that the reader can explore.

This experience flipped a switch in me and I immediately started browsing blogs about Linux, open source software and Hackernews.com. One day I came across an article on lowtechmagazine.com in which the Belgian journalist Kris de Decker reports how he has stopped buying new computers for more than 10 years and works exclusively on old IBM Thinkpads. The vintage models, which can be bought second-hand on the Internet for little money, are still so stable and modular that they can be repaired quite easily (link).

In the following part I explain why this excited me in a philosophical way. It’s a very personal part where I share into my worldview.

With the discovery of this blog, I have found a cosmos of threads that should keep me busy and excided for the next few years. There was the following problem: I had previously read a number of books that shed light on the whole mess of technologization from all sides and which ultimately only allowed one conclusion: We’re screwed. But I didn’t want to accept that. I think it’s much easier to say that we’re screwed than to make constructive proposals, even if they only work on a small scale for the time being and/or are accompanied by sacrifices and limitations. And that’s exactly what Kris de Decker, who has been writing critically and constructively about technology for 17 years, does. “Low Tech Solutions” for “High Tech Problems”. The spectrum of topics is closely linked to post-growth-ideas. De Decker proposes solutions as to what a life with simpler technology could look like in practice.

Transition:

I made another interesting discovery…

…in the archive of the German magazine “Kunstforum International”, which reported on an exhibition entitled “Low Tech” in the Shedhalle Zurich in the year 2000 (link). Here I found a bridge to the fields of art and design.

Research on Lowtech.

“Lowtech is the casual answer to the myths of technology and the needs that an industry associated with it wants to create.” […] “Lowtech is […] by no means just a cheap substitute for more expensive technology, but makes practices accessible that are regularly buried in the fixation on the latest and most expensive.” (link, freely translated)

The Sheffield-based artist group “Redundant Technology Initiative”, which was represented with its works in the exhibition, published a “Lowtech Manifesto” in 1999, which is still available online. This document helped answer a few questions for me as a designer.

High tech artworks market new PCs. Even if they aren’t meant to. Artworks that make use of new, expensive technology can’t avoid being, in part, sales demonstrations. Part of the message of an online video stream, whatever its content, is “Hey, isn’t it time for an upgrade?”. (source)

High-tech art and aesthetics therefore (often unintentionally and very successfully) sell the latest technology. Another paragraph:

High technology doesn’t mean high creativity. In fact sometimes the restrictions of a medium lead to the most creative solutions. (source)

The development of low-tech ideas is about working with limited resources and technical limitations, which ultimately amplifies creativity.

Transition

This reminds me…

Since Monica is a friend, I would mark this blue, as a personal depiction.

…of the graphic designer Monica Losada. She developed an experimental book project (together with Josu Larrea) in 2021 that dealt with the Tool Horizon (a term coined by Petr van Blokland) of open source design software. Basically, the publication shows a wide range of graphic experiments that were created with freely accessible tools. Sometimes she has also misappropriated software: some of her works, including her submission for the DEMO Festival, were created using Microsoft Excel.

In Monica Losada’s work, something special emerges that I would describe as “authentic low-tech aesthetics”. Monica has chosen the hard way, deliberately used selected, very limiting tools and has thus achieved a result that radiates a strong aura precisely because of this inherent creative gesture. Creating artificial low-tech aesthetics with professional software such as Adobe Creative Cloud is pretty easy. But then it lacks of authenticity. The aura of low tech begins to shine when it is combined with a conscious detour, a workaround.

Millipedes have countless feet and yet they are the slowest of all crawling creatures. (Freely adapted from Dio Chrysostom)

Transition

Here I suddenly notice an interesting association…

Creating a connection to ancient wisdom.

…that I would like to pursue further. Maybe Low Tech philosophy emerges from a way of thinking that reaches far back into history and that can be found in Socrates (469 BC – 399 BC). This jolly minimalist wandered the squares of Athens and entangled the people of the city in questioning conversations in which he uncovered their basic assumptions. The result of these conversations was usually the realization that they were wrong in their widely held beliefs. Socrates could also be described, somewhat over-simplified, as an origin of skepticism.

Over the following years, decades and centuries, new philosophical branches emerged from this thinking and continued to weave this thread. In the Hellenistic period, the most important schools of thought were strongly inspired by Socratic thinking and were similar in their core beliefs, but each sought and found their own ways to put Socrates’ skepticism into practice in life.

One figure that comes to mind here in connection with low tech is Diogenes of Sinope. He lived frugally in a wooden vessel and consistently rejected any kind of luxury, although as a philosopher and author he could have lived quite differently. There is this striking legend of the warlord Alexander the Great, who approached the ascetic on the street and asked him for a wish that he wanted to fulfill. Diogenes’ answer was simple: “Get out of the sun”.

Conclusion:

As is so often the case, it was once again a seemingly insignificant event that triggered a momentous train of thought. The dying laptop led me, via many exciting detours, to the idea of setting up this blog. Now that I think I’ve finished this text, I realize what fascinates me so much about Low Tech: It’s the elegant and casual gesture that lies beyond.